The haunting sounds of bamboo pipes have formed a part of the Andean landscape for over two millennia. The Andean melodies most people are exposed to today, however, are a result of centuries of colonialism and the migrations of peoples from different regions and continents. Let’s take a look at how all this happened.

The haunting sounds of bamboo pipes have formed a part of the Andean landscape for over two millennia. The Andean melodies most people are exposed to today, however, are a result of centuries of colonialism and the migrations of peoples from different regions and continents. Let’s take a look at how all this happened.

Many people associate indigenous Andean instruments to the time of the Inca. Flutes are generically labeled “Inca Pan-Pipes” and the images of Macchu Picchu are conjured up in the imagination. While the Incas certainly employed the instruments we know as “Andean”, it is important to understand that many cultures preceded the Inca dynasty, and with those cultures flourished music and instrumentation that the Incas merely inherited. Tawantinsuyu, the Inca Empire, lasted a mere two hundred and fifty years before its demise at the hands of Spanish invaders. Originally from the Cuzco valley, the Incas expanded rapidly, imposed their language (Quechua) and exacted tribute from their subjects. In little more than two centuries, they stretched as far north as southern Colombia, and as far south as the Rio Maule in southern Chile. Invariably, they introduced styles of music and instruments during their conquests. But were getting ahead of ourselves. What about the Pre-Inca civilizations?

There are a number of major cultures that the Incas would have to give credit to. In the highlands of present day Bolivia exist the ruins of Tiawanaku, a culture that was predominantly of the Aymara people. In the coastal regions of Peru, we have the Nazca culture, their artwork often depicting the playing of sikus during religious ceremonies and funerals. Elsewhere were ceramic antaras found in gravesites and tombs. Other fabulous cultures included the Moche, the Huari, Chimú and Chavín. Through numerous excavations, archaeologists have proven that the kena was, in its most rudimentary form, a flute that preceded the birth of Christ.

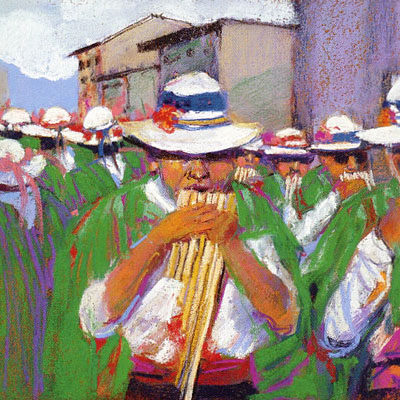

In Pre-Colombian South America, music was a sacred art, a powerful source of communication with the divine world. Religious ceremonies paid homage to the pantheon of deities closely associated with the landscape and weather. The agricultural calendar, such an integral part of daily life, was marked with different celebrations and musical traditions. Prior to the arrival of Europeans there were no string instruments in the Americas. The Andes were dominated by the sound of wind and percussion. The tuning was pentatonic and the melodies were of another world. Many of these traditions survive today in the form of Tarkeadas (Tarka Flutes) Mohoceñadas (Mohoceño flutes) Sikuriadas (Siku flutes) and the dance of the Kena–Kena (Kena flutes). When people ask about “traditional” Andean music, this is what I think of. It is not soft, melodious or soothing. Rather, it is raucous and loud, bordering on discordant. It almost always includes the playing of large bass drums (italaques and wangaras), snare drums, and at least a dozen flute players employing pipes of different sizes and tunings. Perhaps the gods demand this?

Click Below to hear Sikuriadas

Click Below to hear Sikuriadas

[audio:/site/Tropa.mp3|titles=Tropa|artists=Andrew Taher|autostart=no| loop=yes]

When Europeans first heard this music, they were horrified, believing it to be diabolically inspired. They decided to destroy this pagan worship. The conquerors did their utmost to eradicate these traditions. Members of the religious clergy felt spiritually obligated to “civilize” the native. This included prohibiting the playing of Andean flutes. It was the landscape itself, the magnificent and imposing Andes, that saved these traditions from disappearing entirely. The inaccessibility of the land was its salvation. In countries less remote, like Mexico, the conquerors were more successful, and today, there is little left of Pre-Colombian music.

The meeting of Francisco Pizarro and the Inca, Atahualpa, in Cajamarca, Peru, was ostensibly the beginning of the end for the Pre-Colombian era in the Andes. The Spanish conquerors would forever change the Andean world. Through mass conversions and the zeal of Spanish missionaries, a new culture was super-imposed upon the indigenous population. The Spaniards brought their music, their language and their instruments, which contained a heavy dose of Moorish flavor as well as European. Natives were introduced to new, exotic instruments: lute, guitar, harp, violin, accordion, mandolin. Later they would be introduced to brass instruments: saxophones, clarinets, trumpets, tubas. Every year at the carnival of Oruro, Bolivia, , the vast majority of musical bands employ brass. The song-forms are all Bolivian (saya, morenada, llamarada, doctorcito, kullawada, tinku, tonada, huayño, diablada), but the instrumentation is seldom with bamboo. In Huancayo, Peru, the famous huaynos are played with saxophones. In Ayacucho, the cherished instruments for Peruvian huaynos are the guitar and charango. These European instruments all form part of the Andean musical tapestry. Andean music is performed with electronic keyboards and electric guitars, full piece drum sets and electric bass. The popularity of Peruvian “Chicha” music, which combines Andean rhythms and Colombian “Cumbia”, is a good example of this modern adaptation. This picture clashes with our western, romantic ideal of the indigenous people stuck to the past, wearing traditional clothing and leading what we perceive to be “traditional” lifestyles. People are often surprised to discover that the bamboo woodwinds of Pre-Colombian South America, form only a part of current Andean music. This is not intended as a criticism but rather as a revelation.

How can we expect the Andes to be immune to the forces of globalization?

Spanish conquest introduced several major changes to the Andean musical world. First, the introduction of string instruments and, second, the western musical scales: Major and minor keys, sharps and flats. The standard key for most Andean flutes is G major. Nevertheless, the combination of Andean woodwinds and Spanish strings is a fairly recent development. Typically, most people are exposed to the classic Andean sounds of the kena and siku, accompanied by guitar, charango and the bombo. This is emblematic of what musicologists refer to as the “Pan-Andean” movement. Traced back to the late nineteen fifties and nineteen sixties, this followed the migration of rural indigenous people to the large urban centers in search of work, with the introduction of Andean pipes into the urban setting and the inevitable mixture with “criollo” culture. The “criollo” culture refers to the mestizo, or mixed race culture, that is the product of European and indigenous ethnicities. Musically speaking, no instrument better exemplifies this than the charango. The charango is a string instrument that embodies the combination of these two cultures. It is descended from the vihuela de mano (hand-lute), brought by Spaniards from the Mediterranean. The instrument was copied by the indigenous population, and the end result was a new and unique addition to Andean folk music. Many people credit the town of Potosí, Bolivia, as the birth place of the charango. Peruvians, on the other hand, tend to disagree, arguing that the charango comes from Ayacucho, Peru.

The “Pan–Andean” sound that has come to symbolize Andean music for most westerners, can trace its lineage back to several monumental groups. In La Paz, Bolivia, a group called “Los Jairas” popularized the new music and was one of the first ensembles to introduce Europeans to the Andean sound. The group included the Bolivian master, Ernesto Cavour, on charango and a swiss flautist by the name of Gilbert Favre, on kena. During my travels in Bolivia I was told that it was “El Gringo”, Gilbert Favre, who showed Bolivians not to be ashamed to play the kena. Such was the colonial stigma that had continued up until that time.

Meanwhile, in Chile there was an important movement going on called “La Nueva Canción Chilena” (New Chilean Song Movement). Young musicians, artists and students, were discovering Andean instruments and beginning to incorporate them into their music. Groups, such as Inti-illimani, traveled to Bolivia to learn about Andean folk music and bring the style and instruments back to Chile. Artists like Quilapayun, Victor Jara and Violeta Parra, used the new song movement as a social tool. The songs were infused with politically charged rhetoric. Highly critical of influence from the North (USA), Chilean musicians made Andean instruments and Andean music synonymous with the political left. The simple act of wearing a poncho became subversive. The culmination of this movement was the election of socialist president, Salvador Allende, in 1970.

Following the overthrow of Allende, in 1973, Andean music and instruments were forbidden in Chile. The music had become closely identified with the left, and the military government saw to its eradication. Many artists, like Victor Jara, were disappeared or murdered. The folk groups Inti-illimani and Quilapayun, were exiled. Inti-illimani took up residence in Italy and the popularity of Andean music in Europe continued to soar. At this time, due to the lack of visa restrictions, many musical groups from Bolivia, Peru and Chile began migrating to Western Europe. Street performing in those early years proved financially viable. The possibility of making a living as a musician in the home country was remote, and many musicians dreamed of success in Western Europe. By the early eighties, the flight of musicians to the west increased. Now many Ecuadorians (particularly from Otavalo) joined the migration. Eventually, there was probably a South American street band in every major European city. I used to joke with some of my band members that they had been seen by people all over the world (“I saw you playing music in Venice last summer…yes, I am sure it was you, you had the same long hair…”).

One anecdote worth recounting, is the chance meeting of Simon and Garfunkle, in the late sixties, in a Paris subway, with the Andean group Los Incas. Here the American duo first heard the timeless Peruvian classic “El Cóndor Pasa”. They pursued by adorning this ancient melody with English lyrics. It would prove to be one of their most popular songs: “I’d rather be a hammer than a nail…”. The “Pan-Andean” movement was well on its way.

Bolivia continued to be a source of development for the “Pan-Andean” style. Famous groups, like Savia Andina, brought a high degree of professionalism to the new sound. Virtuoso performers executed stylized interpretations of Andean folk music, using the charango, kena, siku and bombo. In Cochabamba, the group Los Kjarkas, blended regional melodies with polished vocals. Their love ballads became the latest manifestation of the new sound that proved incredibly popular with young people. They established schools (Escuela Kjarkas) throughout Bolivia and neighboring Andean countries, to promote their new musical style. My friend, Augurio Quiroz, once said that Los Kjarkas, with their prolific compositions and endearing love songs, were the Beatles of the Andes. I think he was right.

By the late eighties, in part due to the saturation of musicians in Europe, many Andean artists set their sights on the USA. It was more difficult to enter the US legally, however. While some musicians were fortunate enough to come directly, others came from Europe, where many now had residency and legal status. Some groups worked their way north from the Andes, passing through Central America and Mexico, before entering the US, sometimes illegally (this could take years). In the nineties, there was a veritable explosion of Andean groups that began in the large city centers (New York, San Francisco, Chicago, Boston, LA). The groups multiplied rapidly. What began as one group would inevitably split (often following financial differences) into two, two into four etc… This was no longer a few musicians playing for tips on a street corner, but rather a collection of competing small businesses that had one sole objective: profit through the sale of CDs.

Andean music today continues to undergo its process of transformation. Andean instruments are now “Latin American” instruments, played and enjoyed by artists in Mexico, Central America and elsewhere. To the uninformed, these instruments are generically associated with “Latino” folk music. It is important, however, not to lose sight of the origins. The “Pan-Andean” song movement is the stereotypical representation of Andean folk music. Abroad, it has evolved to be primarily an instrumental music, showcasing the Andean woodwinds above all. In Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador, on the other hand, the most popular groups always highlight the vocal dimension, singing the world’s most popular song-form: the love ballad. As part of the “Pan-Andean” movement, there are groups in Ecuador that play the Bolivian charango. Bolivians, in turn, play the Ecuadorian rondador. Groups from Peru interpret Ecuadorian san juanitos and Bolivian sayas. Excellent musicians, from Chile, play the folk music of Bolivia and Peru. The charango, originally from Bolivia, is now found throughout the Andes in Chile, Ecuador, Argentina and elsewhere throughout Latin America. The “Pan-Andean” movement transcended national and regional boundaries.

Sixty years after the marriage of Andean woodwinds and European strings, Andean music has attained a small place in the world stage. From relative obscurity, the folk music of the Andes has reached a global audience. Due to economic pressures and subsequent migrations, there have been Andean groups in all four corners of the globe. Andean musicians have taken their music to places as far away as Mongolia and the Middle East, Korea and Australia. One could argue, to some degree, that Andean music has been a victim of overexposure. How else to explain a parody of Andean street bands by the creators of South Park?

Hopefully, Andean instruments will continue to experience a growing interest and excitement from those who feel drawn to this ancient sound. The pipes of ancient South America continue to be used by native populations, and their popularity shows no signs of disappearing. Virtuoso performers of different nationalities are numerous, their efforts to play pay tribute to the enduring appeal of these timeless instruments. Ultimately, Andean music is a vehicle to understanding the history of a continent, its people, and their struggle to maintain a connection to the past and establish a true, independent identity.

– Andrew Taher